Confessions of a Serial Game Jammer (after ~40 jams)

I just came across a great talk by Chris DeLeon regarding game jams and long term improvement: “Long-term improvement doesn’t happen in a few days per year”. In the talk, Chris warns those who do 4 brutal days of game jam a year as their main practice, that it is not enough, and speaks about why regular practice is important.

I agree and have more to add. I have some of my own observations and opinions as a very frequent gamejammer. I’ve done ~40+ game jams so far as a mostly-solo jammer, usually 1 or 2 jams a month depending on the duration of the jams (some are 1+ week long jams), and availability of more interesting jams. Here’s what I learned from doing jams much more frequently (4-10 brutal days a month for the past 3 years):

1. Regular practice and using Jams as tests: Yes, regular practice/exploration outside of jams is important. Jams are a great way to test/measure those skills that you practice. Think of the regular practice as homework, and jams as the exam. In the regular practice/exploration, you can just explore an aspect or technique (e.g. just do some artwork), while in a jam, you’ve got to put together the whole game (if solo). If you do jams frequently enough, then the jams do become part of the regular practice.

Or as a sports analogy, if you’re training for a triathlon, think of the jam as the triathlon event, and the regular gamedev practice as the sessions that you go swimming, biking, or running. Regular practice can also fit as a part of a longer jam…

2. Longer Jams: There are longer jams, such as One Game A Month, which allow you to do your regular practice while having a much more relaxed deadline/goal. These may be helpful for those who can’t do brutal short intense jams.

It’s good to vary it up so that you don’t get into the mindset of only being able to do 48-72 hour projects. The challenge in these longer jams is to keep the scope manageable, and keep motivated and disciplined. I think it’s good to mix up the length of jams that you participate in so that you can grow in these different areas.

For the art or sound side, there are those “30 days of _______” challenges that come up, such as NaNoWriMo, 3December, Inktober They aren’t game jams, but they have a community for you to share your daily creation with, even if you can’t do it every day. Getting encouraging feedback helps with…

3. Motivation: The thought of future jams and upcoming jams can give you motivation for learning new stuff well, so that you can use them during the jams. Also, when motivation is lacking, just commit to practicing your craft 5+ minutes a day. The hardest part is just sitting down and opening up the tools you use for making games/art/sounds/music. Once you get started, it’s harder to make yourself stop after those 5 minutes than it is to keep going.

4. Plateau? Nah. Jams can help to break you out of a plateau or kick you back into the gamedev itch after a lull.

Or if you are actually doing jams as your only gamedev, then I think the key is to create a personal challenge to stretch yourself for each jam you do (besides for doing jams more frequently).

Even after 40 game jams, I still learn something new, try a new technique, or hone a different skill in every jam. Have a goal or personal challenge for that jam; e.g. “I want to try adding a dialogue system this time”, or “I want to practice this new and funky type of 3D texturing that I heard about”, or “I want to focus on my story writing skills this time”.

More importantly: This personal goal/challenge has to have a higher priority than just finishing the jam or necessarily doing “well” in the jam. After finishing a few jams, you’ll get over the overrated importance of finishing the jam, and be concerned more about creating a game that is worthwhile to finish and has something new or interesting to add.

My personal challenge in this coming weekend’s jams (1) (2) is to make a 2D game (I usually make 3D games and am horrid at 2D). So right now, that goal is forcing me to learn 2D gamedev techniques that I can use at the jam. I know the game is probably going to be crummy, but I’ll learn a ton from the experience.

5. Check out the other jam games. You can learn a lot simply by playing through the other jam games in the jam from a reverse engineer’s point of view. A great thing about them is that they’re free and show what can be created in that time period.

Think about what you might do differently to make the games better. Find things that work well in other games. Especially pick up on new and noteworthy experimental things that other games do, though not necessarily well executed, but have potential. One good way to start is to write a feedback comment for a jam game is “What I loved about this game is….”

Did you like an aesthetic/mechanic that a game had? Then figure out how to make that aesthetic/mechanic, or ask the developer how they did it in the feedback comment that you give them.

6. Clean code: If you want to improve your efficiency by jamming, try to keep clean code and write it quickly, for as long as you can during the jam. Try that as a personal challenge, marking the proportion of the jam that you kept cleanish code. Only resort to crazy-spaghetti-code when you get to that point where you think “oh crap, only x hours left!!”

Try to improve your personal record of how far you can get through the jam without going dirty. Always keep in mind that you may want to continue the game after the jam. Contrary to what you might think, over the course of a few jams, you’ll notice that you’ll code more efficiently, or do things a bit differently in ways that save time.

On the flip side, if you don’t care about improving your clean coding efficiency and just want to focus on finishing the jam, then mess things up intentionally so you don’t slow yourself down with clean/well-engineered code. Use crazy/obscure/obscene variable/method/class names. Create a Globals class and put tons of stuff in there. For small projects, it sure is quicker. It will help you get over your inclination to want to write clean well engineered code, and get things done the quick and dirty style.

7. The Importance of Aesthetics vs Gameplay mechanics: So you made a jam game, and want people to play it. All else being equal, do you think more people who have only your game’s cover thumbnail image (and no other info about your game) are going to click on the game with the great mechanics and story but programmer art, or the game with the lovely polished stylized aesthetics but poor mechanics? From what I’ve observed, the latter gets far more clicks and plays in game jams, and are rated higher whether they deserve it or not.

That said, some of the most memorable jam games that I’ve played were actually Twine games, but I fear that the average player doesn’t have the patience to read through all that text.

It varies by the structure of each jam, but I find that the biggest factor in getting people to play your jam game is the cover image, and then the screenshots/GIFs/videos. It has to stand out against all the other games in the jam and on the jam’s site and on social media. In a large jam, games without interesting cover images are easily lost. A game’s amazing gameplay mechanics are wasted if no one is even going to click on the game or download it after seeing the screenshots. On the flip side, a good aesthetic has the effect of making up for lack of good game mechanics – I’ve seen time and again where it makes players think it is a better game.

If your game is lacking in good aesthetics, then make an extra effort to at least make an outstanding thumbnail cover image for the jam’s site. That is a whole topic in itself that I cannot cover in this post.

Unfortunately, I don’t usually have time to make a game’s thumbnail cover image for the jam’s site until the final minutes of the jam, or even until after submitting. I’ve learned that having good in-game aesthetics naturally helps make it easier to create a cover image quickly: take a screenshot of game assets posed dramatically, and put on some typography. It also makes it easier to take good screenshots/GIFs to share and promote the game.

8. The “Right Way” to Jam: Too often, I’ve heard other jammers say that the “right way” to do game jams is to get the mechanics down first, with placeholder everything, and then make the art/assets and polish. That makes a lot of sense if your goal is just to finish a playable game, but I don’t think that necessarily result in a “sexy” game that people will click on, since the aesthetics are prioritized last in that order.

Nowadays, I typically start with, and spend most of the time on the aesthetics. I pretty much start by picturing moments, interactions, and feelings based on the theme, and picturing a screenshot of a quintessential moment in the game. After making and seeing the interesting aesthetics, I am then inspired to come up with story/interactions/gameplay/levels. Sharing the aesthetics with others and seeing how they react to it helps to inspire the rest of the game.

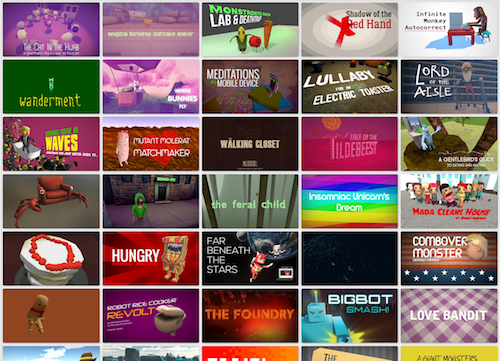

Often I don’t know exactly what the gameplay mechanics or story will be until the final quarter of the game jam. In some cases, this isn’t until the final “make it work” hours of the jam, where I go into quick and dirty mode, and the real magic happens at miraculous speeds due to time pressure, lack of hesitation, lack of perfectionism, lack of concern for cleaning up code after the jam, and lack of sleep. Some of my best work and/or most critically acclaimed work has come from these final magic hours, doing gamedev the “wrong” way:

- Lord of the Aisle – the gameplay mechanics, waves, dialogue, all came in the final magic hours. This game jam game, which had some idiotic gameplay mechanics and an interesting main character aesthetic had 200+ Youtube videos made about it, and even pirated by a dozen other game sites. I spent most of the time making the main character, a random shopper generator, and random supermarket shelves generators.

- Infinite Monkey Autocorrect – the game is almost entirely aesthetics with no real game mechanics, but was voted #1 for Innovation and #2 for Humor, out of 1637 games in Ludum Dare 34 (72-hr Jam). WTF is wrong with the voters, right? It’s pretty, but is it even a game?

- Lullaby For An Electric Toaster and Shadow of the Red Hand – the levels are all made in the final hours, which is an obscene thing to do for platformers, where the levels are the game. Most of the time was spent in the aesthetics/artwork. Lullaby was voted #1 out of 21 for LetsCookJam, and Shadow of the Red Hand was voted #10/1574 for Innovation and #11/1574 for Theme, out of 1574 games in Ludum Dare 35 (72-hr Jam). Both of these games had wonky controls, yet they did “well” in the jams and were popular with YouTubers.

I’ve found it a good idea to keep the game mechanics relatively simple and unoriginal for jams. From my observations, very few players, especially YouTubers, have the patience to learn novel or experimental mechanics. Written instructions are almost useless except for the 1 in 10 players who will bother read them.

I’ve tried making jam games with more novel or experimental mechanics, and it is usually not received as well as my games with simple mechanics.

I think each jammer needs to discover their own “right way”, based on their styles, skills, and experiences. Don’t just blindly accept other jammers’ “right way” as your own. Even your own right way will change with time.

8. The Idea Fairy: I have to admit, once I got the game jam addiction, I haven’t really been able to stick with a single non-gamejam game project of my own. It’s not that I can’t work through longer projects (I routinely do longer projects for my clients), it’s just that shinier new game ideas keep coming along. I have several game jam games that I want to turn into full games, but keep getting distracted by the next shiny game jam, which produces another shiny new idea that I want to turn into a full game.

Because there are so many game jams to choose from nowadays, it’s hard for me to resist not jamming. And when I return to my old in-progress full game projects after being interrupted by a game jam or two, I feel like they are already obsolete, or my heart is in a new idea.

It sounds a lot like the Idea Fairy comic by theMeatly. It’s not a problem unique to game jammers, but frequent game jamming sure does exacerbate the problem. Beware!